Reviewer’s Introduction

This book was written in 1995. The reviewer has only just encountered this author and this theory of autism. No doubt, the theory has been substantially developed since 1995. The author is currently a Professor of Psychology at Cambridge University and is still involved in autism research. Baron-Cohen also appears to be involved with a charity called the Autism Centre of Excellence. This Charity produces a very nice series called Transporters, designed to help children with autism work on recognising emotions. [1]

I was drawn to this theory because in my own theoretical thinking I had developed something a bit similar. I have been thinking about the theory that autism is caused by deficits or damage in sensory processing networks. I don’t find this all that satisfactory. I think my reason for this is that my sense, working with autistic children, is that the issue is cognitive. It is like they, and I am focussing here on young people whose profile is very classically autistic, don’t get an aspect of the social world. I also have not noticed a lot of evidence that young people with autism are having issues with sensory process. Obviously; their sensory experience is invisible to me, but, I just don’t find the explanation convincing. Yes; I know young people with autism, and possibly more complex profiles as well, who are distressed by too much noise and who, for example, like to wear noise cancelling headphones. But, I speculate, even this does not establish a sensory problem. It could be that the sounds, for example of people speaking, are reaching the cognitive apparatus of their minds completely without distortion, but they present difficulties to the cognitive system, so it is better not to hear them. Of course; I may have missed young people who have especial visual sensitivities. But, again, autistic behaviour does not seem to me, simply anecdotally, to correspond e.g. to light stimuli. One classic autistic young person I worked with, for example, was just as autistic indoors or outdoors, and under various indoor lighting conditions. He did not seem to be in sensory discomfort. I have experienced once or twice some of the issues thought to be part of the sensory story for autism; for example sending visual signals to the auditory processing centre, or the other way around, I actually forget. (While using LSD). But this did not, I think affect my social functioning in any way. None of this is very scientific. But, my sense is that autism is a cognitive matter not a sensory one, which is not to say that there may not be issues with sensory signal processing circuitry in the brain.

In my own thinking then I was looking for a cognitive explanation. But, I also have a sense that the kind of classical psychological models of the mind that I was exposed to, memory, attention, induction etc. do not provide a basis to explain autism. And, one cannot explain autism as some kind of deficit in ‘executive function’ or intelligence, because that is the field of ‘learning difficulties’ and yet autism is clearly something different and specific. Thus I started to think in terms of “modules” in the mind, (and maybe brain). I am probably inclined to think in terms of modules due to my background in software development. Lots of systems are based on modules, which are separate but which interface with each other and support the functioning of each other. It is a natural and very effective way of organising a system. Why would the brain/mind not have evolved like this? Thinking along these lines I began to speculate about a module which was to do with understanding the social world. And, then, I came across Baron-Cohen and Theory of Mind.

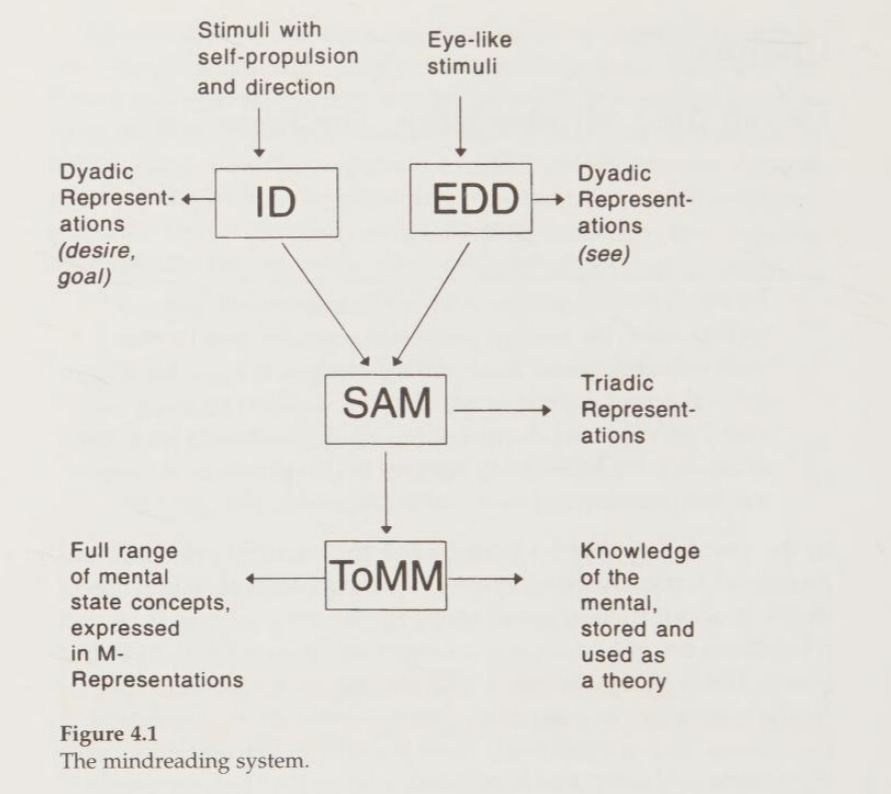

Baron-Cohen positis a module called ‘Theory of Mind Module’ which is responsible for understanding (based on probability) the states of mind of the other. People who have this module can “mindread”; that is they can make good guesses about what another person may, at any one time, be thinking or believing, supposing or dreaming. It can deal with pretence and deceit and distinguish between facts and beliefs. (Joe says X but actually I think he thinks Y or Mary sincerely believes B as if it were true even though B is false). It is important to note that Baron-Cohen’s theory is not just about a general ‘social module’. Indeed he mentions one scientist who proposes such as model and criticises it as “too broad”, partly on the grounds that some autistic people may be not impaired in some social areas. In Baron-Cohen’s theory, ToMM (theory of mind module) depends on a separate module which is about shared attention, called SAM. Underneath this module in the system are two further modules; EDD or Eye direction detection module, and ID or Intentionality Detector. The model is explained in terms of evolutionary biology and modern neuropsychology which uses various types of brain scan studies to associate function with brain area.

As usual with these reviews we provide a brief summary of the argument.

Foreword

John Tooby and Leda Cosmides.

Psychology has moved on from broad-brush concepts such as “attention”, “short-term memory”, and “induction”. It is becoming a natural science. Specific functions are thought to have evolved through natural selection and these functions are handled by separate, interlocking, “modules”. The location of these modules in the brain can be identified. The social world we inhabit is not a “given”. It is already pre-interpreted to us by the actions of all these modules on raw data. There are modules for; recognition of facial muscles as representing emotions, language processing, (a module which comes pre-built to recognise “noun phrases” and “verb phrases”), sorting out the world into bounded 3-D objects, detect eye direction, and the ToMM – theory of mind module – which builds up a representation of what the other, in a social dialogue, is thinking, intending, feeling and hoping, (and so on), and many others. Baron-Cohen will present a theory about this Theory of Mind module and how damage to this specific module is what ’causes’ autism.

Chapter 1 – Mindblindness and Mindreading

Mindreading is the ability to represent states of mind that we or others might hold. Imagine what life would be like if you lacked this ability. The author gives an example;

Peter is seen coming into the bedroom. He walks around, then walks out.

How can we interpret this? Well; we might think that Peter has lost something and is looking for it. Or, maybe he heard a noise coming from the bedroom and came in to investigate,

These are all examples of mind reading. (Perhaps based on our own knowledge of what goes on in our minds), we can consider what might be happening. We attribute mental states, intentions and desires, to Peter. But someone without this ability cannot do this. How could they explain this? For example, by temporal-regularity; Peter does this every day! Or, (in a dig at behaviourists), by recourse to some explanation about reinforced behaviours. But; these won’t help a person survive in the social world.

Mindreading is a capacity which has developed evolutionarily.

Chapter 2 – Evolutionary Psychology and Social Chess

The author provides the metaphor of “social chess”. Human beings evolved a “social intellect” in order to deal with the complexities of social living. One can get on, and achieve reproductive success, both by supporting the wider social group and also by exploiting and out-maneuvering individuals within it. The ability to think about social situations has an evolutionary basis. This capacity developed in early humans from 3 million to 10,000 years ago. The author acknowledges that this “Machiavellian” concept of social interaction and brain evolution has its critics but argues that it is a “strong contender” for the theory which best explains brain evolution. He also acknowledges that cooperative social interaction also involves mindreading. Some critics, of course, have emphasised that it is cooperation not competition which has driven humanity forwards. (Mutual Aid. Kropotkin).

The idea of this chapter is to establish the certain social-intellectual faculties have developed as a result of evolution within a social species which lives in communities.

Chapter 3 – Mindreading. Nature’s Choice

Alternatives to mindreading, or the Intentional Stance, include: the Physical Stance, the Design stance and contingency. The Physical stance works for explaining e.g. biological phenomena but not human behaviour; clouds cause rain. The Design Stance is related to function and design and can explain things in simple terms. The computer has a Delete button which … deletes text, because this is what it is designed for. Again; one can see limited scope here for explaining human behaviour. Contingent or behavioural explanations can sometimes work; this man is raising his fist at me, time to take some defensive measures. But, behavioural explanations do not work in the many social situations where there are no, or very few, behavioural clues. However; the author suggests, animals use this method for navigating their world.

The author argues that mindreading is not just used in making sense of behaviour. It is also an essential part of understanding communication. He gives some examples, including this dialogue, to illustrate his point:

Woman: I am leaving you.

Man: Who is he?

Without intentionality, understanding what the man might have meant is not possible. Understanding communication depends on representing to ourselves what participants in a dialogue might believe, think, wish for etc..

A second and key aspect of the role of intentionality (mindreading) in communication is the speaker taking a view on what her listener already knows and supplying information adapted to this.

Mindreading is the best, indeed the only real, mechanism, which evolution could have come up with, to solve the problems of social interaction and communication.

Chapter 4 – Developing Mindreading: The Four Steps

In this Chapter Baron-Cohen presents his theory.

The theory of mindreading must be able to explain how humans solve problems and how human ancestors solved problems, if it is to be a viable theory of evolutionary psychology. (And, as per a previous chapter, natural selection is the only theory in town for human evolution).

The author proposes 4 components to the ToMM:

1) ID. Intentionality Detector. This subsystem decides if an object is an agent and ascribes goals and desires to agents. This orange stripey blob moving towards me is an agent and it wants to eat me.

2) EDD. Eye Direction Indicator. This subsystem detects eyes. It notes if they eyes are looking at self or at something else. The subsystem understands that gazing or looking means seeing.

3) SAM. Shared attention mechanism. Triadic. Specifies relations between Self, Agent and an Object, (which could be another agent). [Mummy sees -> (I see the bus)]. Note that this also means that Mummy can see both I and the bus. SAM can use any sense but especially EDD. (Sight).

ID can feed into SAM as well. E.g I want the apple.. [Mummy sees -> (I want the apple)].

EDD is used to impute goals.

4) ToMM. Theory of Mind Module. Includes epistemic mental states: believing, knowing, pretending, deceiving, guessing, dreaming and imagining. Examples:

John believes – (It is raining). This is an example of an “M-representation”.

Note that this implies an understanding that it does not necessarily have to be raining.

Normal 4-5 year olds understand these complex situations. Tales like Snow White which include such situations – Snow White believed she was buying an apple from an old lady when in fact the apple seller was really the evil Queen, are understood.

SAM is essential to ToMM.

The author outlines normal infant development:

birth – 9m ID and basic EDD

9m – 18m SAM

18m – 48m ToMM. Start of pretend play.

The author prefers the term neurocognitive mechanisms to distinguish his theory from an earlier theory that the mind and brain are modular but essentially accepts the same general idea of different “modules”.

The author leaves open to what extent these “modules” are fully innate and to what extent they can be developed by learning. But it seems clear that he intends that at least they arrive (develop) in a basic form, innately.

On the following page we reproduce the schema of the author’s model.

The author says that ToMM gets started by converting SAM into M-representations. Triadic representations are converted into M-representations. SAM is necessary for ToMM. Let’s try to think of some examples, (these are my examples):

1)

SAM: [John sees -> (I see the girl)] nb. this involves EDD. I look at John’s eye direction and figure out that John can see the girl, see me and follow my eye direction.

M-Representation. John knows – [I see the girl]

2)

SAM: [Mummy sees -> (I see the bus coming)]

M-Representation. Mummy knows – [I see the bus]

and Mummy knows – [the bus is coming] ?

3)

SAM: [John sees -> (I want the apple)].

M-Representation: John believes – [I want the apple]. Note; at this point I could pretend to want the apple. I could make John believe I want the apple, even though I don’t really. We can see see how M representations create the scope for pretend play, and also deceit.

The author supports his theory with reference to experiments though these are only mentioned briefly. It is out of scope here to do the necessary background research to evaluate the author’s truth claims. Certain aspects seem to the reviewer to be plausible. I think I can remember “discovering” the reality of M-propositions; this was a secondary and reflective knowing, when I was perhaps 10-12, but it still hit me and it seems very fundamental. ID seems plausible simply from observation of infants, as in fact does SAM; the author cites experiments where the infant is seen to monitor the gaze of the other. It appears the infant is checking that they are both looking at the same thing.

It is important to note that the author believes that these are distinct mechanisms and that they have a location in the brain.

Chapter 5 – Autism and Mindblindness

Blind children who have no EDD can mindread. So EDD is not essential to mindreading. Therefore the inability to mindread is likely to be caused by damage to the SAM or ToMM modules. Baron-Cohen says that experiments show that ID is not damaged in children with autism. For example; they use the word “want” in their spontaneous speech, whereas they do not use words related to mind-states very often. Autistic children also use the word “see”. They can detect when a person in a photograph is looking at them. This is evidence that EDD is undamaged in children with autism.

Writing in 1995 the author says that autism affects 4-15 children in every 10,000. Taking his higher figure that is 0.15% of the population. Now the figure of the UK is 1%! [2] A growth of a scale of 6.5 x since Baron-Cohen’s estimate in 1995!

There is evidence that there is “massive impairment” in SAM in autistic children. For example they do not use pointing to draw someone’s attention to something. SAM problems are apparent in the auditory channel as well; children with autism do not modulate the intonation of their speech. The author presupposes this is because they have no sense of the other as an interested listener.

SAM feeds into ToMM. I think the suggestion is that the child can infer mental states in the other based on introspection of his own, and SAM. If I feel sad when I look at the broken toy and both Mum and I are looking at the broken toy together (SAM), then Mum probably feels sad as well. So; if SAM is impaired – no ToMM can develop. “My idea is that ToMM is triggered in development by taking triadic representations from SAM and converting them into M-Representations”. The shared attention of SAM is the basis for building M-Representations. In Chapter 8 the author discusses this question of whether introspection is the basis for Theory of Mind. He does not in fact say that it is. He suggests that possibly, the knowledge gained by introspection is “ascribed to others”. If I understand; I note by introspection that if I lose my toy I feel sad. I see that Sally has lost her toy. I apply this knowledge to her and conclude that Sally must feel sad.

“The robustness of this finding suggest that in autism there is a genuine inability to understand other people’s different beliefs”. This refers to an experiment which tested whether children who had mistakenly (but reasonably) assumed that a Smartie tube would hold smarties, but which, in fact, held pencils, would be able to understand that other children would also believe (wrongly) that the same tube contained Smarties. When reading this I feel a slight cold shudder. My other work is in the field of International Relations. [3] Is the whole of the European political class autistic?

Some children with autism show simple mindreading ability, but not more complex, of the order of “Anne thinks that Sally thinks X”. In general understanding “knowing” can be shown to be easier than understanding “belief”. Reduced mindreading ability is also apparent in the reduced ability to predict emotions based on belief; but some autistic children are not impaired in their ability to predict emotion based on desire or situation. Children with autism also have difficulty distinguishing between appearance and reality. Shown a rock made to look like an egg, normal children say things like: “It looks like an egg, but really it is a rock”. Autistic children were more focussed on the perception: “It looks like an egg”. “It is an egg”. Thus people with autism are more likely to be dominated by current sensations and perceptions.

Chapter 6 – How Brains Read Minds (and a word on unnecessary animal experimentation)

The author proposes a sixth sense organ – introspection of mental states, which exists in humans but not in animals and which evolved in evolutionary terms. We can note that this sense is accepted in Buddhist literature, (and has been since early times – that is perhaps since the first century BC). However; the main focus of this chapter will be to locate the proposed cognitive functions of the earlier chapters in physical locations in the brain.

Baron-Cohen locates EDD in a particular area of the brain called the superior temporal sulcus. Tragically, Baron-Cohen cites a 1990 study [4] which provided evidence for this in monkeys by getting the monkeys to perform a gaze related choice connected to two photographs, then removing part of the brain, and then getting them to perform the task again. After the “operation” the monkeys could not perform the task. The cruel study Baron-Chosen cites references a book in which the same conclusion is reached based, apparently, on recordings of “live from single cells in awake, behaving monkeys”, which appear to mean non-invasive recordings. The finding is also supported by evidence from humans who are known to have damage in this area of the brain. In this era of MRI scans, and which were commercially available before 1990, experiments such as the one cited by Baron-Cohen which cause untold suffering to primates while producing conclusions which can readily be established by other means can only rationally be explained by a senseless and vicious desire to inflict cruel suffering on animals. By citing this unnecessary and cruel experiment Baron-Cohen discredits himself and his work. It is very unfortunate.

We continue to review this work with a heavy heart. Objectively speaking, that the author of the text lacks the wisdom to avoid basing his work on unnecessary animal cruelty does not mean that all his conclusions are invalid. Had Hitlter perchance invented a useful medical device, we would still use that medical device, if it saved lives.

Baron-Cohen also references another work which talks, in a sinister way of “lesion studies” involving animals. I doubt that the lesions in laboratory animal experiments referred to in Kling and Brothers 1992 arrived accidentally. Indeed the theme is pervasive; “…other frontal lobe lesions do not produce such significant social changes in experimental animals, de Bruin 1990”. I can’t locate de Bruin 1990, but earlier work by de Bruin seems to have involved ‘experiments’ involving causing damage to the brains of rats. The term here, used by Baron-Cohen, “experimental animals”, is indicative of the attitude. One can ask; when does an animal stop being an “animal” and become an “experimental animal”? What is the ontological difference between an “animal” and an “experimental animal”? If none; why not just say “animals”? “Experimental animals” is an obvious rationalisation and attempt at a PR gloss to disguise the horrors of what they are doing. *

Baron-Cohen locates the ToMM in the orbito-frontal cortex, this time based on a rational study involving human subjects responding to stimuli while in a SPECT brain scanner, (a device which detects altered blood flow in the brain).

The tragedy here is, of course, that Baron-Cohen could establish his thesis without citing unnecessary and cruel animal experiments and in fact does.

Chapter 7 – The Language of the Eyes

The author advances a thesis that humans read emotional states in the eyes of others.

[The online copy of this book which I am reading is missing two pages here]

The purpose of this chapter seems to be to develop the thesis that the proposed EDD system is a very important part of the cognitive architecture of human beings.

Animals have eye detection. However; the author says “it is not clear if non-human animals engage in this reflective stance after joint attention”. By “reflective stance” he means the subject asking, “what is he [the other] interested in?”. If I understand correctly, this seems to belong to a higher level of the proposed system. Only in SAM can ID output – detection of what the goal of the other is – be used by EDD so that EDD can read eye direction in terms of an agent’s goals or desires. From Chapter 4:

“There is some evidence that is consistent with the model according to which, when EDD is linked up to ID via SAM, eye detection is interpreted in terms of the mental states of desire, goal, and refer, (the latter being a special case of goal).”

Chapter 8 – Mindreading Back to the Future

The author says that the evidence from primate observation studies is that many primates probably have EDD and ID, but not SAM or ToMM. However; these is some evidence that chimpanzees may have SAM. But, there is also observational work based on noting that young chimpanzees do not associate gaze with attention which refutes this. But there is some possibility of SAM in one species of chimpanzee, the bonobo.

The author discusses the relationship at the cognitive level between executive function and ToMM. He argues that because executive function problems such as “conduct disorder”, and obsessive-compulsive disorder can be present even in people with good ToMM it cannot be the case that ToMM is secondary to executive function (because it would be damaged too). The two exist independently of each other.

In defence of his proposed ToMM system with its subcomponents as described the author argues against the broader concept of a general “social module”. We would support him in this. He has presented detail experiment results (discounting irrelevant animal experiments) which support his idea of discrete modules. Some kinds of social understanding may not be impaired in people with autism.

The author subscribes to Chomsky’s view that there is a pre-built innate “language module” in human beings; that learning languages is not just some generalised learning process but is based on this specific innate capacity – a specific module. The author discusses the evolutionary development of language and mindreading while noting that the discussion is speculative. He suggests that without theory of mind, other than for basic communication, there would be little point communicating. He prioritises theory of mind while accepting some mutual bootstrapping between theory of mind and language in development.

Baron-Cohen discusses various alternative views. In one variation, which accepts Theory of Mind, imitation is said to play the key role in forming theory of mind. Baron-Cohen criticises this idea on the grounds that the evidence for a deficit in imitation in autism is inconsistent. However; he does not rule out a role for imitation altogether, just argues that its position in the system may be more complex than the proponents of the imitation theory propose.

For those of us who work with Intensive Interaction, which is based around “attentive imitation”, the idea that imitation is a key deficit in autism is interesting. Intensive Interaction can be understood as a training in imitation, not, of course, mere copying, but an attentive process of feedback to how the other is communicating. which allows the other to feel “heard” and, via imitation, to be part of a communicative exchange. In as much as it can lead to improvements in communication could one argue that it is remedying a foundational aspect of Theory of Mind? An alternative view, (still trying to understand how Intensive Interaction can be understood in terms of Baron-Cohen’s ToMM theory), might be the opposite; Intensive Interaction makes use of undamaged imitation skills as a basic for communication. In this case no actual improvement needs to be posited; Intensive Interaction is simply finding an intact function and using that for communication.

Other theories of what might cause mindreading not to develop are mentioned; for example, a general motivation to communicate can be posited. Baron-Cohen then focuses on two main ‘rival’ theories. It seems that Baron-Cohen believes his theory is superior because it has a distinct module for eye detection and a distinct module for ‘shared attention’. He believes that experimental evidence shows that these are distinct modules. For example, he refers to experiments which monitor the gaze of young children. secondly, he refers to ‘declarative pointing’. This is the developmental stage when children start to point at an object, and then turn back to check that the other person is looking at the same thing. Baron-Cohen believes this represents a distinct stage, but one which is necessary for the development of mindreading.

Baron-Cohen asserts that autism is a developmental disorder. People “with” autism may develop. At the same time problems with the ToMM may be associated with problems with executive function, even though the two systems are independent. The author is wise to say that he is not claiming that ToMM issues are the only factor in autism. However; he wants to assert the centrality to his proposed theory of mind model and assumed deficit to explanations of autism.

There is a nice account in this chapter of a successful US academic, Temple Grandin. Temple Grandin is autistic; though based on the account she does have some functioning ToMM since at the age of eight she was able to engage in pretend play. According to the account Temple Grandin has learned to compensate for her lack of theory of mind by developing her own bank of studies of behaviour, which enable her, based on recognising similar behaviours, to predict what someone will do. This is perhaps rather like the system a modern DSLR uses to calculate exposure; it refers to a database of situations and tries to find a matching one.

Reviewer’s Conclusion

One strength of this work is that the theory is developed scientifically, with reference to repeatable studies. This reviewer is not in a position to evaluate the evidence especially where it is used to resolve a conflict between one theory and another. However; some of the experiments described do provide direct support for the author’s case. Unfortunately, as we have discussed, the author supports his case with reference to animal experiments. His case, however, could be made without citing these experiments, even on the material he presents. It is disappointing to see this lack of awareness that causing unnecessary suffering to animals is problematic. (Not least because the author repeatedly reminds us how we should not extrapolate from one animal species to another).

If I am honest, the theory appeals to me because I can see, in my own life, especially as a teacher, how I make use of the features described in the theory and other examples of their applicability. I sometimes deliberately use my eye direction to signal to someone what my goal or desire is, for example that I would like him to turn the lights off. I’m just seeing if I can communicate my goal or desire with my eyes. When I do this, I feel like I am exercising a specific function. The moment of shared attention; a child pointing at the moon and saying to me, “Look can you see the moon”, which is ‘shared attention’, also has a feeling of activating a specific function. I encounter examples of communication where, in the face of uncertain intention of communication, it becomes hard for someone to work out what the other means. I once worked with R. a boy of 5 with a very classic (and ‘severe’) autistic profile for one week as a support worker in a school. R. seemed to be cut off from the social world, not because the world was too violent on his senses, but because processing the meaning of the social world was too much. That was just my sense of him; nothing scientific. Having said that, I immediately want to add that during the week, possibly linked to the fact that I was practising Intensive Interaction with him, we did take part in a turn-taking activity. It was a little painful for him, and not the smooth and pleasurable experience it might have been for a ‘normal’ five year old, but still he initiated it. On another occasion also he demonstrated possession of SAM. He was very upset, after having been told off by a class teacher for destroying the brick tower of another boy, and I could see he wanted to kick off. But; he didn’t know me very well. (I was, unfortunately, only agency staff). At one point he basically looked at me to see how I was going to react when he let it all out, and started having a meltdown. This implies SAM; [Justin sees -> (my intention to kick this door)] and even, possibly, ToMM; how is he going to evaluate this? (I don’t have any evidence he was thinking about my mental state and not my behaviour; simply that is how I interpreted his behaviour). This is interesting, because it suggests that in a moment of high intensity R. could activate these functions, at least the shared attention. It is a truism that “people with ADHD”, (a psychiatric diagnostic category with far less grounds than autism), exhibit the attention deficit less when engaged in certain tasks or activities. (Again; I have seen this. A young man with attention problems in class, possibly linked to intellectually being young for the tasks, showed high attention when building a model aeroplane with me, an activity he had chosen, and enjoyed). This point is not observed or discussed in the book which is at times a little uncomfortably psychiatric in its language of deficit and even, once, ‘deviant’. Overall, however, it is clear that Baron-Cohen is making a very serious and focussed effort to understand autism and this with the intention of helping autistic people.

We find the theory presented in this book plausible. I don’t feel I have enough background to evaluate the model as a whole with its proposed development pathway and relationships, for example, the point that SAM is a necessary condition for ToMM. But, the broad outlines of the theory are persuasive. The core idea, of mindreading, the ability to make a good guess as to the mental state of another person; what they think, believe, know, suppose, pretend, imagine, dream, guess or may be deceiving us about, being deficient in autistic people and this is the core factor in autism, is plausible.

* Perversely in the final chapter of this book the author groups together human children and primates in one table to compare facilities. He fully understands that human (children) are just like animals. Which means that (logically) “experimental animals” are just like humans. He seems unable to draw the obvious conclusion from this. He must be missing some component of his brain.

Mindblindness: An Essay on Autism and Theory of Mind. Simon Baron-Cohen

1995 MIT

I read this book online here: https://archive.org/details/mindblindnessess0000baro/page/114/mode/2up

The book is available on Amazon but not in electronic form:

Notes

1.

https://resources.autismcentreofexcellence.org/p/transportersuk

2.

3.

4. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/002839329090050X Campbell et al. 1990.